Promoting Well-being at the Intersections of Neuroscience and Arts-Based Research

by Jennie Gubner and Sydney Streightiff

Introduction to Awe Walks… and why they are good for our brains

In Fall 2020, Neuroscientist Dr. Virginia Sturm published the results of a new scientific study that showed that going on 15 minute awe-walks could promote brain health in healthy older adults. Dr. Sturm is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Neurology and Psychiatry and Director of the Clinical Affective Neuroscience (CAN) Laboratory at the Memory and Aging Center at UCSF in San Francisco, California. As a specialist in researching emotions, her goal was to tap into the positive emotion of awe—an emotion akin to childlike wonder—to offer individuals an accessible, affordable way to live healthier lives. While her study focused on older adults, she emphasized in her media communications that awe walking is something that can be done by people of all ages.

Although the study was designed prior to the COVD-19 pandemic, the results are particularly appealing in a time when people around the world continue to seek out strategies to address the everyday social and emotional challenges caused by prolonged isolation. After its publication in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Emotion, the study made a significant splash in both scientific and popular media and was covered in articles published by major news outlets like the New York Times, and The Guardian. These kinds of studies are exciting as they don’t involve expensive pills or technology but teach people how to tap into certain emotions and simple activities that can help produce wellbeing.

The study itself was organized as an 8-week-long randomized control trial where 52 healthy older adults were asked to go on weekly 15-minute walks. Of the 52, some were asked to go on regular walks and others to go on awe walks, in which they were tasked with looking for things that inspired feelings of awe. The analysis of the data collected (including surveys, self-assessments, and “selfies”) showed that going on walks with the specific intention of looking for awe resulted in more emotional well-being than just walking. Compared to the control group, the awe walkers experienced both more joy during their walks, as well as heightened prosocial positive emotions (ie. compassion, admiration, gratitude) and decreased stress in their daily lives in general. Typical of this kind of scientific publication, Sturm’s article features detailed charts and statistics but has little room for illustrating examples of the sensory moments of awe encountered by participants on their walks.

At the University of Arizona, Jennie Gubner works as an Assistant Professor of Ethnomusicology and as Chair of an Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Applied Intercultural Arts Research. Sydney Streightiff is a PhD student in this program who holds a Masters in Oboe performance. Central to the values of this innovative new MA/PhD program are a commitment to finding ways to generate research outcomes that are usable by communities in addressing contemporary social issues. The program also seeks to foster arts-based research and amplify what Elliott and Culhane have called “imaginative practices and creative methodologies” (2016) to generate scholarship that is experiential and accessible to public audiences. As two educator-researcher-artist-activists (See Capous-Desyllas, Morgaine 2018, viii), we share an interest in building bridges between the arts and the health sciences. When we learned of Sturm’s study, we began wondering how applied, experiential, and arts-based research methods might be useful in bringing more visibility to these exciting new findings about awe walking.

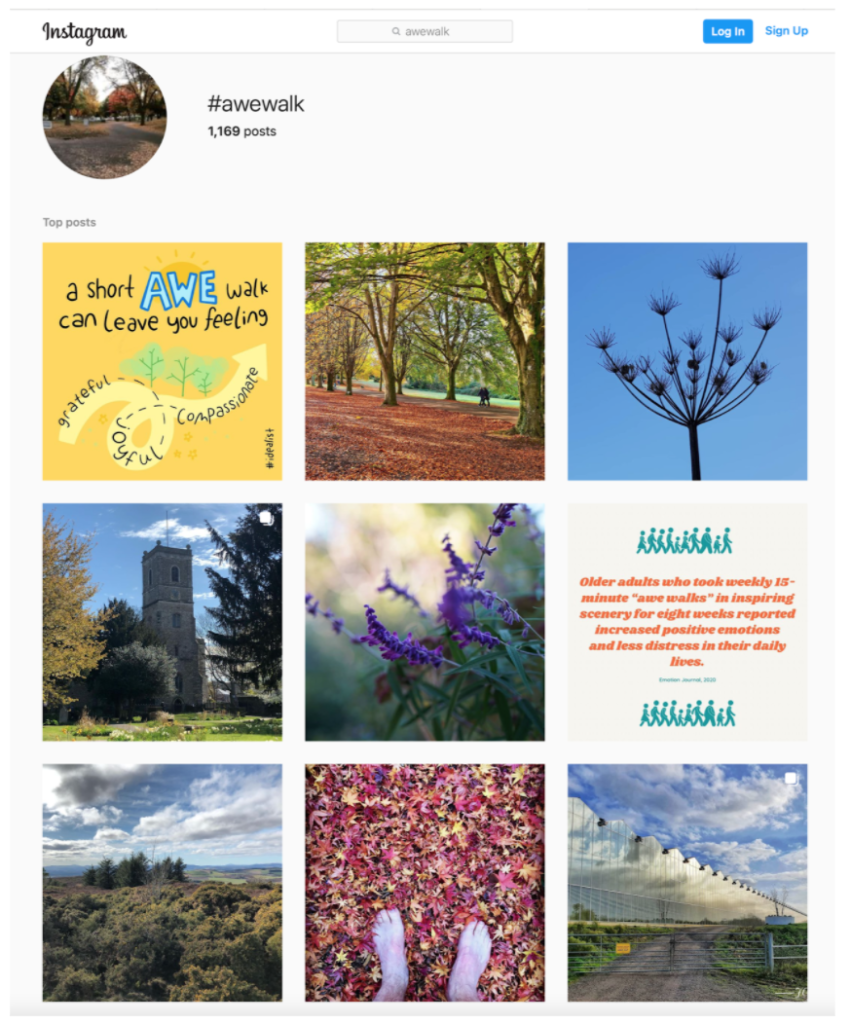

In her previous research (See Gubner 2018a; Gubner, Smith, Allison 2020) Jennie used creative, experiential short films as a research approach to broaden and humanize understandings of dementia and creative aging. Having had previous success using creative approaches to educate about issues in health sciences, she wondered how creative documentation and sharing about awe walks might encourage more people to learn about and engage in this new wellness activity. Sydney, on the other hand, had prior experience using art making as a wellness modality to address the stress that comes from professional training as a musician. When she learned about awe walking, she was curious to know whether it might be possible to combine awe walking with other art making modalities that are also known to promote well-being. When Jennie spoke to Dr. Sturm directly about the project, Dr. Sturm mentioned that #awewalk had started appearing as a new hashtag on Instagram as people were eager to share their experiences of awe with one another. Their reflections on that conversation inspired the following project.

After speaking with Dr. Sturm about her study, our team spent Spring 2021 testing out different ways to craft bridges between awe walks and different forms of creative documentation and creative social engagement. Thinking about the collective fatigue experienced by university students, faculty, and staff after two semesters of online learning through Zoom, we were particularly interested in thinking about how creative sharing around awe walking might offer new wellness-inducing avenues for social connection for university communities. Connected to the broader project’s theme of encounters between ethnography, arts and pedagogy, we sought out to explore: 1) how creative and arts-based research methods could be used as tools to document and enhance encounters with awe 2) how shared creative documentation of awe walks might facilitate positive social encounters between others and act to bring visibility to the idea of awe walking.

We invite you to join us on a walk through the four phases of our exploration of awe over the past six months, categorized loosely around the themes of ethnography, arts, and pedagogy. As an exploratory and experimental investigation, this process evolved organically. Far from having our paths mapped out clearly from day one, we allowed our process to wander down side roads and unmarked paths, some detours leading back to the main path and others to exciting new trails.

Phase 1: ETHNOGRAPHY- Tuning into Awe through Ethnographic Observation

Our first task as a team was to try awe walking ourselves and to reflect on different creative approaches to documenting and sharing moments of awe with one another. Drawing from sensory ethnographic methods, we decided to first use photography to produce images with the goal of allowing others to experience, or be inspired by, some of the “sensoriality” of awe walks (see Pink 2009). What do awe walks feel like? How might an image, or a set of images, be used to recall or bring someone else into a moment or series of moments of awe? Could the creative documentation of awe walks encourage more awe walking for the walker and/or those who saw their creations?

The goal in setting out to document awe was not to perfectly translate an experience of awe from one person to another. We know well that in ethnographic writing, filmmaking, or other modes of storytelling, we can, at best, evoke elements of experiences but cannot ever perfectly recreate lived realities. Understanding this, one of the benefits of creative arts-based approaches to research is the ability to embrace the creative retelling of an experience. With this approach, the narrator worries less about recreating the moment exactly as experienced and instead on how creative approaches to conveying knowledge can help evoke certain elements or feelings of that moment for someone else. Creative approaches to ethnography thus offer many liberating possibilities for bringing others closer to our embodied experiences in the world. Approaching ethnography through creative modes of documentation (like drawing or photography) also allows us to look in new ways, noticing different details and allowing us to tune in to elements in our surroundings that might be overlooked if observing with a more scientific eye (See Causey 2016, Sacks 2020; Tausig 2013).

In the context of this project our goal was not to assume that awe can be perfectly bottled and shared in a photograph, but that perhaps photographs (or other approaches to creative documentation) can be carefully curated to evoke some element of the awe experienced, and perhaps to inspire the viewer to want to seek out similar or comparable experiences of their own. As a project intended to reach beyond academic communities, we see creative ethnographic methods as a tool to generate snapshots of knowledge that can in turn be shared with broader public audiences.

In her previous research (Gubner 2018) using sensory ethnographic methods, Jennie found it productive to use a set of predetermined themes in her fieldwork as a way of tuning into different elements of lived, sensory experience around a larger research question. Inspired by this approach, our team spent our first month going on weekly walks guided by three themes that we felt might be relevant to the overall topic of “awe” situated in the desert landscape of the American Southwest. The themes we chose were texture, light, and color. Each week, we shared images reflecting these themes from our walks with each other over a WhatsApp group, as well as wrote weekly reflections in a shared Google Doc. What follows are some snapshots of the images shared through our WhatsApp group as well as some selections of text taken from our shared reflections.

___________________________________________________

Notes from our Awe Walk Diaries

Sydney – 12.10.2020 – “I was surprised to see that almost all of my texture pictures were grey with the exception of the kumquat tree. I think the monotone helped me see the texture better because it is not something I typically look for on walks.”

Jennie 12.21.2020 – “Cameras are all about capturing light, but how can I use my camera to document awe-inspiring moments of light in such a way that I can invite another into my experiences. On one of my light-themed awe walks, I realized what I found most awe-inspiring were the many variations in light on a December afternoon , how light changed so much depending on tiny movements in position, or how light changed so quickly in time. What inspired awe was the dynamic quality of light, and not light as something static. Thus, I decided to play with collage and montage to tell these stories allowing me to show variation over time. Particularly in the late afternoon during the Fall season of Tucson, I found an abundance of light-related awe moments everywhere I turned.”

Sydney – 12.21.2020 – I was most surprised by this week because light is a theme that I really wanted. When I think about light I think the view that brings me the most joy is a sunrise or a sunset, which is why I included the picture of the sunset behind the clouds. I love the way that the picture came out and it reminds me of home because of how often I stood outside looking at this exact view growing up.

Jennie – 12.30.2020 – Looking for color was not as immediately awe-inspiring as looking for light. Initially I found myself wondering if these themes were constraining as opposed to liberating, and if I had made a mistake in suggesting thematic walks. As I walked, I challenged myself to focus more intently on details, and subtle differences. Like a camera lens pulling into focus, I found myself starting to notice different patterns of colors and variations in colors around me. I decided on this walk to focus on shades of green, thinking about how many shades of green I could find in the desert, a place more characteristically portrayed through yellows and browns.

Jennie – 12.31.2020 – On a later walking adventure–now more tuned in to the theme of color— I honed in on purples. I noticed that the process of assembling these montages only reinforced my feelings of awe of the incredible colors of the desert. Unlike the light walks, where I was instantly impressed, I found that my color walks became more meaningful the more I processed them and shared them with others. I keep asking myself how the desire to share awe shapes our experiences of it. I tried a few walks without a camera, and found I actually lost focus. The task of documenting awe has seemed to provide a process through which to keep my mind concentrating on these themes and thinking about how to creatively share them. As an ethnographer interested in visual research methods, I think about whether I’m motivated to take these photographs to document and share knowledge that is meaningful to me and that I think can bring joy to others, or because I am a product of a “need-to-have-my-reality-validated-on-instagram” generation. I’d like to think it is more of the former, and that processing and sharing these moments allows me not only to share them, but also to relive them, just like meaningful moments in fieldwork that I film and edit to tell stories about my encounters with music. As with ethnography, there are always pieces lost in translation. Do these images inspire awe for others? I wonder…

Sydney – 12.31.2020 – Throughout the previous month of Awe Walks, I find myself wondering if I can pinpoint what creates awe in myself and recreate it or if part of experiencing the emotion comes from the unexpected. As I explore new places to walk I have found that giant expanses of space do not necessarily trigger awe and I often have to ground myself in the environment. For example, the mass of clouds pictured above is made up of smaller clouds that when combined cover the majority of the sky in this shot. It reminded me of pointillism and the idea that day-to-day life is made up of little events that create an overall experience for the day.

Throughout this month I have had the chance to walk in both Tucson, AZ and San Diego, CA, and found that different triggers gave me a sense of awe. San Diego is a place where I have lived my entire life and could describe the streets in intense detail while Tucson is a place that has a million places still to be explored. My walks in San Diego were often accompanied by family and I found that I was drawn to objects that were altered by people that had walked the same path or were seemingly out of place. During a walk on Christmas day with my sister, we found a tree that had ornaments placed around it. Attached were instructions to take an ornament home to decorate and bring it back to the tree to share with the community.

_______________________________

Observations & Reflections on Phase 1:

1. Having easy, broad themes to follow provided a fun and engaging point of focus for weekly walks, making each week feel new and different. As the weeks passed, we found the themes layered onto one another, so instead of one theme replacing the other, we found ourselves noticing elements from all the themes previously explored. We saw this as an example of how themes help us “tune in” to elements of our environment in productive and compounding ways.

2. It was fun to select images from our themes, creatively edit and curate them, and share them with one another through WhatsApp. It was uplifting to revisit moments from our own walks and to share them with others in hopes of encouraging them to get outside. Revisiting our own images also motivated us to go on more walks.

3. Receiving aesthetically evocative images from each other reminded us how beautiful our natural environment is and incentivized us to go on walks. It also offered a positive way to stay connected and socially engaged in a time of near total social isolation and Zoom overkill (Arizona was in complete lockdown due to soaring COVID-19 cases during December 2020).

4. Although we looked forward to walking and it never felt like a chore, we also were motivated to walk from a sense of accountability we felt towards a shared project, not wanting to let each other down.

5. Writing reflections on a shared Google Doc was an important exercise in generating data from an intellectual standpoint about our project but did not produce the same positive feelings that we felt when sharing images. Similarly, it was more appealing to learn about each other’s awe walks through carefully selected snapshot images than through lengthy, reflective text. Much like sharing dreams in detail, we realized that the in-depth reflective details of an awe walk were always more interesting to the walker than to the recipient of the narrative.

6. The more we went on awe walks, the more we started seeing awe in other places. For example, in looking back at our shared WhatsApp chat, we began sharing images from other parts of daily life that were not during our walks (for example a view of the mountains taken from a window, or an image of planets from a telescope). This is consistent with what Dr. Sturm discusses in her work, saying that awe breeds awe. The more we focused on this emotion, the more we began seeing it all around us.

________________________________

Phase 2: ART: A Detour in Connecting Art Making and Awe Walking

Art making can be used as a powerful tool for working through emotions and conveying experiences in the world. As a mode of therapy, art making has been shown to increase positive health outcomes not only for a broad range of acute patient needs, but also for health care workers in processing the stress of their jobs (Moore 2013). Art making has also been shown to induce a “creative high” as a proven method for decreasing stress (Curl 2008). As a research methodology, art making methodologies like drawing can work with existing ethnographic methods to help creatively understand and convey lived experiences (Causey 2016; Taussig 2013).

In discussions with Jennie, Dr. Sturm explained that awe breeds awe, in the sense that the more you connect with the emotion in your daily life, the stronger the health benefits should be. Walking is just one easy way to connect with awe but awe is also often found in other realms of life, such as through art and spirituality (see Keltner and Haidt 2003). Inspired by this conversation, our team wondered if adding art making to awe walking could potentially enhance the positive effects felt from awe walks. Our idea was that if we processed our awe walk experiences through an art-making activities, this would give us a new opportunity to reconnect with our experiences of awe and enhance those emotions by engaging in a creative practice. In this detour of our investigation, we sought to embrace and combine artistic practice both as a way of looking (ethnographic method) and a recipe for wellness (art as therapeutic process). In both cases, these approaches encourage participants to let go of the societal rules of what makes a drawing “good” and instead focus on the process of creating and conveying ideas through a creative lens (Sacks 2020).

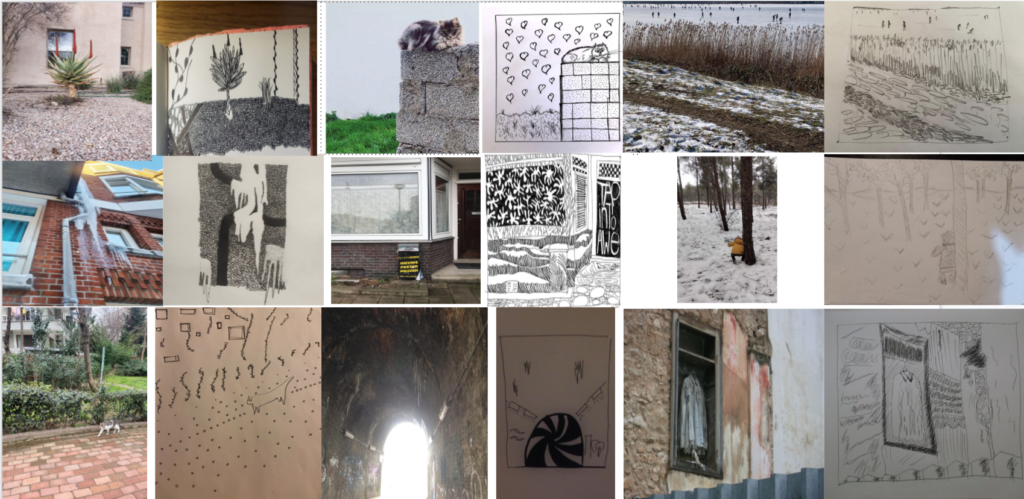

To test this idea and to engage with awe beyond the mode of photography, we spent the next few weeks going on awe walks and then producing something artistic. We started by taking a single image from our weekly awe walks and turning it into a Zentangle. The purpose of a Zentangle is to create an artistic meditative experience through drawing. The idea of Zentangles was initially brought to us by Sydney who started using it as a non-judgmental creative outlet to combat the stress of perfection in music performance. To create a Zentangle, one creates an outline of an image in pencil and then fills the space with simple doodles such as a checkerboard or polka dots using a black marker. In creating our Zentangles, we appreciated the opportunity to take time in our week to further process our walks while engaging in a meditative creative practice. That said, there were certain limitations, one being the time needed to complete an artistic assignment and the other that the Zentangle recipe is quite strict, and Jennie found herself wishing she could use more colors in her drawing.

The second form of art making we explored was inspired by object collection in which the members of our team collected objects found on our walks and then created any kind of artistic output inspired by those objects. This assignment was broader in what could be collected and what each member of the team would do with it. Both members of the team collected rocks on their walk but manipulated them in different ways. It was interesting to see that each member of the team was drawn to different art forms. Jennie was drawn to oil pastels and Sydney was drawn to sculpture.

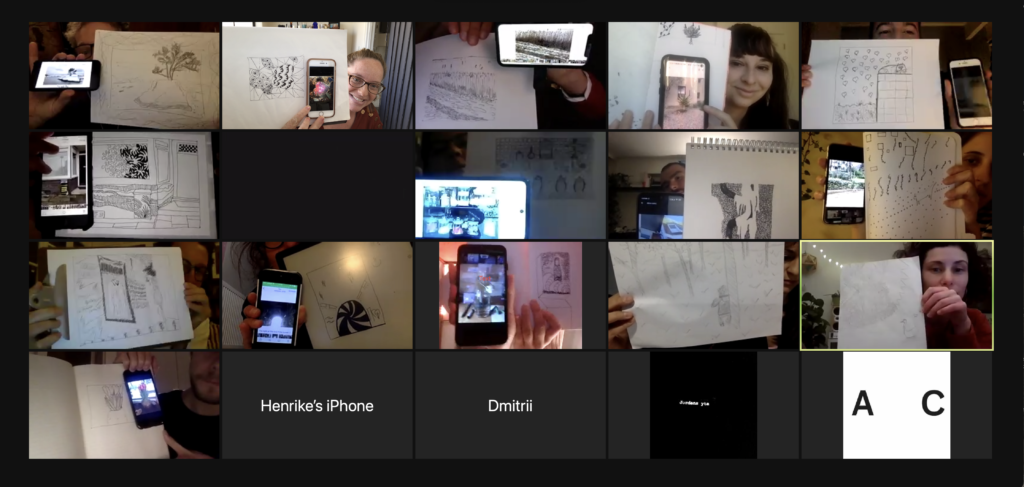

After engaging in our own exploration of making art from our awe walks, we tried out our art making approach with the larger international Encounters research group. To do this we asked members to go on an awe walk and to come to our Zoom meeting with a photo from that walk, along with a pen and paper. Once together on Zoom, we explained the research behind awe walks and then invited everyone to join us in making a Zentangle using the photo they brought. We put on music, and everyone worked independently for about 20 minutes. The resulting images were exciting and brought the photos they had to life. We then spoke with the participants about their experience of reconnecting with their awe walks through this drawing exercise. Some of the feedback we received was that it was nice to be on Zoom without having to talk, and to be gifted some time to be creative and to engage in a meditative drawing practice. The participants enjoyed sharing their photos, although some wished they had had more time to complete them. We asked everyone to send us their images and photos, with which we made the collage below.

_________________________

Observations & Reflections on Phase 2:

- In incorporating art making exercises into our awe walking explorations, we observed that compared to cell phone photography, art making lead us to be more judgmental of our own artistic abilities, which took away from the positive and wellness-inducing goals of the practice.

- Finding the time to do extra art projects posed another challenge. Since it was difficult for us to find the time, we think these exercises might be daunting when working in larger groups of people with different schedules and amounts of free time.

- In soliciting informal feedback, we found that some artists felt the short online Zoom art making session was not enough time to produce a final project. It seemed that for trained artists, it was difficult to focus on art making as a process and not a product.

- In recognizing that art making can sound daunting to many, we decided that going forward it might be best to keep artistic assignments broad in order for participants to participate creatively in ways that speak to them without the pressure to use unfamiliar tools that could cause stress or anxiety.

- While we noticed some challenges about art making prompts, we also recognize that many elements of these assignments were very positive and enjoyable. We would encourage creative groups of awe walkers to embrace and explore the potential of artistic prompts, if/when the group feels comfortable and has time for this added layer of engagement.

__________________________

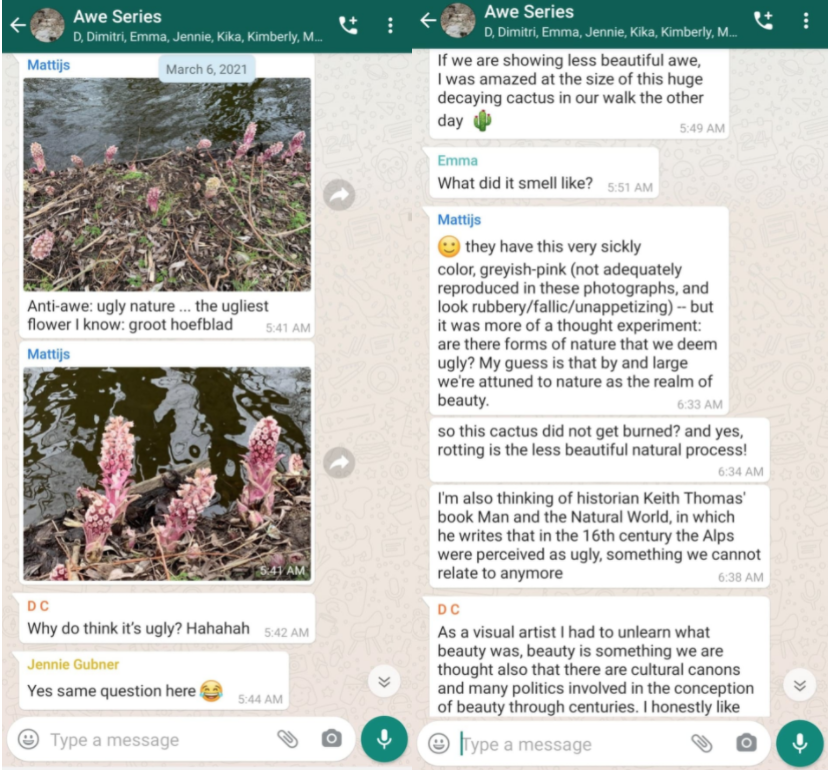

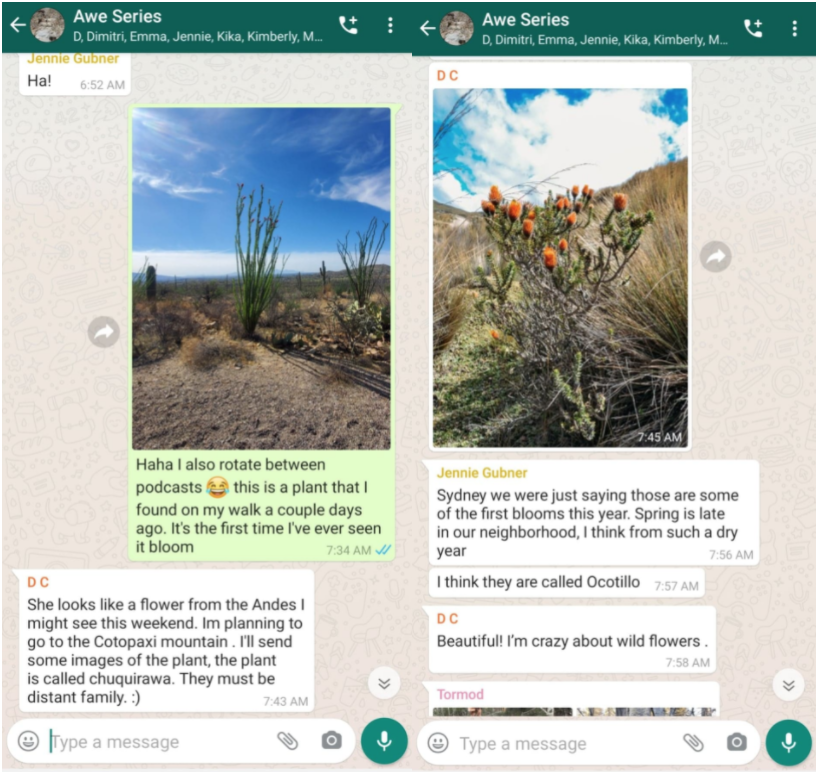

Phase 3:PEDAGOGY: Incentivizing Awe-Walking through Creative Sharing Groups

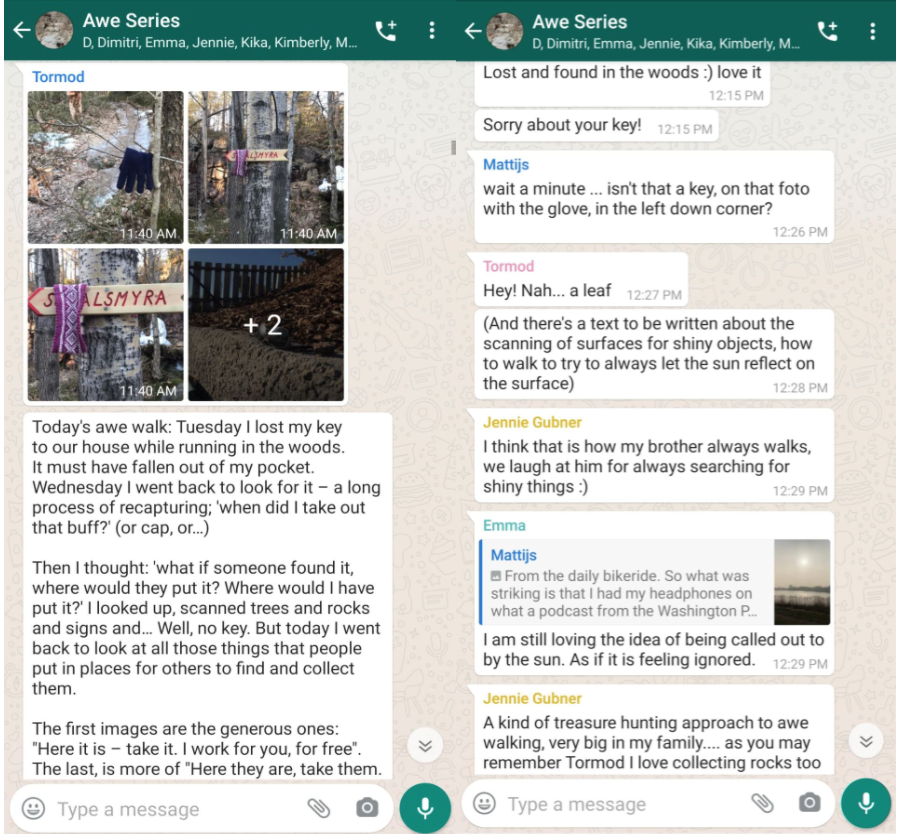

Inspired by the virtual community on Instagram that came from the initial press from Dr. Sturm’s article, the team decided the next step would be to invite others to engage in a virtual awe-walking social group. Our hope was to gain more perspectives and to see what worked in hopes to design models for awe walking groups in the future. The group we cultivated consisted of members from the Encounters group as well as individuals from our own personal networks (9 participants total). The goal of this group was to participate in a month-long WhatsApp group dedicated to walking and creatively documenting awe walks. To run the group, we offered new thematic prompts each weekend and invited participants to share their thoughts throughout the week. The weekly themes we used were meant to explore different senses as well as encourage the participants to explore other arts-based practices. Instead of focusing on more meetings on Zoom, we hoped this approach would create an informal and positive space through which to engage in awe walking and positive social encounters. The following snapshots of our group chat bring the reader into some of the conversations that emerged over the course of the month.

On week 1, we asked the group to go on an awe walk without any specific theme and to share images on the chat. This first prompt generated multiple conversations rich with unique images from each other’s worlds. With such a broad prompt the reflections seemed deeper and more self-reflective. During the second week our group focused on the theme of sound where we encouraged participants to share the audio from one of their walks and have others guess what was happening. While our team found this to be a natural transition because of our background as musicians, we found that conversation in the chat slowed down. We imagine that part of the reason for this is that they may not have been as appealing to all, or perhaps it was a more complex task to ask people to tune into sounds instead of imagery. Nonetheless, what we noticed was that when one person posted, it encouraged others to do so. It seemed there was a shared enjoyment in connecting over the images/sounds/videos collected, and a desire to support one another’s posts through comments, reflections, or image responses. We found this trend continued through the following weeks of texture and color.

_________________________

Observations & Reflections on Phase 3:

- In looking for ways to promote awe walks in a group setting, we found WhatsApp to be extremely effective. The chat offered an accessible and informal way to engage with others, and seemed to encourage conversations about awe as people received phone reminders to walk and to share their experiences with others.

- The chat acted almost like the childhood game of telephone in which members were often inspired by an image or comment posted and would then offered their reflection on similar themes.

- Much like the complex prompts of art making, making the prompt too specific or the ask too big (ie create an artistic output) seemed to lead to a drop in participation, likely due to a lack of time.

- When asked to tune into awe using other senses, for example sound, the chat became quieter. Our team believes that this has to do with our participants being less familiar with aural observation and documentation, compared to photography and video.

- As the weeks went on we found that the chat quieted down. This could be because of more specific prompts or because the leaders themselves were distracted by other busy life events (one had a baby, the other was finishing her MA). This showed us the importance of maintaining enthusiasm and motivation to keep these kinds of groups active.

_________________________

PHASE 4: Invitation to an Awe Walk

In and beyond our university, there are growing efforts to find productive ways to bring knowledge from the arts and health sciences together toward goals of promoting wellness and well-being. We believe our work contributes to these growing conversations, as well as to conversations in and beyond academia trying to address the social isolation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide.

Our goals in developing this project were:

1) To inspire people to think about imaginative ways to engage with one another around awe walking and other wellness-inducing practices.

2) To think about how creative and arts-based approaches to research might help amplify and enhance conversations coming out of scientific fields like neuroscience.

The observations we have presented are descriptive and reflective more than prescriptive. We hope they serve to jumpstart conversations with others around ways of expanding and enhancing our work. After 6 months of exploration, we see much potential for using creative methods to promote recent neuroscience findings about the health benefits of awe walking. We see this paper as the beginning of an ongoing project.

We are eager to invite others to explore with us and share from your own encounters between awe walking and creative forms of documentation and sharing. Our next goal is to develop some creative awe walking groups at the University of Arizona as part of a campus-wide initiative dedicated to promoting the role of arts in healthy aging. We offer the following “recipe” to invite others to build their own creative awe walking social circles. While we offer these suggestions as one way of getting started, we encourage our readers to imaginatively reinterpret these rules to fit the needs and quirks and preferences of their own community.

Bibliography

Capous-Desyllas, Moshoula, and Karen Morgaine, eds. 2018. Creating Social Change through Creativity: Anti-Oppressive Arts-Based Research Methodologies. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Causey, Andrew. 2016. Drawn to See: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Curl, Krista. 2008. “Assessing Stress Reduction as a function of Artistic Creation and Cognitive Focus.” Art Therapy 25, no. 4: 164-69.

Elliott, Danielle and Culhane Dara. 2017. A Different Kind of Ethnography: Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Gubner, Jennie. 2018a. “The Music & Memory Project: Understanding Music and Dementia through Applied Ethnomusicology and Experiential Filmmaking.” Yearbook for Traditional Music 50: 15-40.

______2018b. More than Fishnets & Fedoras: Filming Social Aesthetics in the Tango Scenes of Buenos Aires & The Making of A Common Place (2010).” Sound Ethnographies 1/1: 171-186. URL: http://www.soundethnographies.it/07.Gubner.pdf

Gubner, Jennie, Smith, Alexander K, and Theresa A. Allison. 2020. “Transforming Undergraduate Student Perceptions of Dementia through Music and Filmmaking.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 68(5): 1083-1089.

Keltner, Dacher & Jonathan Haidt. 2003. “Approaching Awe, a Moral, Spiritual and Aesthetic Emotion.” Cognition and Emotion 17, 297-314.

Moore, Martha H. 2013. “Trauma Therapists and their experience of zentangle” PhD Dissertation, Capella University.

Pink, Sarah. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sacks, Kyra. 2020. ‘Drawn in the field’, entanglements, 3(1):7-30

Taussig, Michael T. 2011. I Swear I Saw This Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press

0 Comments